In the midst of a global obesity epidemic, is it time to stop funding research on what diet works the best for weight loss and disease prevention? It sounds bizarre. Diet controversies still reign. Low-carb proponents still battle against their entrenched low-fat counterparts. Some experts, however, claim that this war has run its course and should end. The provocative plea was made eloquently by Sherry L Pagoto, PhD in a recent JAMA editorial. Pagoto is a psychologist and obesity specialist in the Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. In her piece, A Call for an End to the Diet Debates, she refers to research suggesting that several popular diets, including low-carb and low-fat plans, have been proven equally effective, thus negating any need for further comparative trials.

In the midst of a global obesity epidemic, is it time to stop funding research on what diet works the best for weight loss and disease prevention? It sounds bizarre. Diet controversies still reign. Low-carb proponents still battle against their entrenched low-fat counterparts. Some experts, however, claim that this war has run its course and should end. The provocative plea was made eloquently by Sherry L Pagoto, PhD in a recent JAMA editorial. Pagoto is a psychologist and obesity specialist in the Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. In her piece, A Call for an End to the Diet Debates, she refers to research suggesting that several popular diets, including low-carb and low-fat plans, have been proven equally effective, thus negating any need for further comparative trials.

Based on the relevant research to date, Pagoto is declaring a tie and asking the combatants to stand down. She argues that further trials will not help us fight obesity in any way because we already have diet choices that would work, if only people would follow them. In her view, adherence is the issue. If we can lose weight and reduce cardiovascular risk with either low-carb or low-fat plans, all that matters is that we pick one and stick with it. Since millions have failed at this, she reasons, we should devote our resources to helping people adhere to either diet. She states that “behavioral adherence is much more important than diet composition,” so we can do more to solve obesity by studying behavioral factors that promote long-term adherence.

Why is adherence so difficult?

Pagoto’s point about adherence is well-stated and important. After all, no diet will work if it isn’t adhered to. Why people struggle to maintain long-term dietary change should absolutely be a focus of further research. We already have some clues, however, as to why adherence is so challenging.

If you ask most people what it means to “eat healthy,” they’ll say it means avoiding foods high in fat. To lose weight, they’ll say, “eat less fat, cut calories, exercise more.” Nutritional authorities have drilled this mantra into our heads so long and loudly that we can mumble it unconsciously like meandering zombies. Or over fries and a milkshake while mustering up the resolve for another low-fat, calorie-restricted attempt. Many have tried and failed to lose weight this way. When we strip fat from our diets, the balance shifts toward adding carbohydrates and removing protein. Do this for long, especially while exercising more, and the forceful hunger it creates can obliterate our capacity for self-denial. In affluent nations where food is ubiquitous, this strategy can prove impossible for the most motivated and strong-willed among us. Public health authorities and institutions have maintained this low-fat party line for too long, in denial of both scientific findings and the utter lack of large scale success. Despite great effort to stick to low-fat diets, many of us give up on weight loss altogether after repeated heartbreaking failures.

Or we may try cutting carbs. Increasingly, people say they know they should cut carbs to lose weight. They may even say they successfully lost weight going low-carb but gained it back after succumbing to delicious carbs yet again. Turning down bread, pasta, and dessert seems unsustainable for some. We grew up with these foods as part of the fabric of our lives. Everyone ate them on every occasion. It doesn’t seem right that we should be denied such convenient, palatable, and comforting foods. In talking with people who tried unsuccessfully to lose weight on low-carb diets, they report that despite feeling full on low-carb meals, they eventually gave in to an unyielding desire for luxurious, high-carb foods.

In my opinion, based on published research and observation, people fall off the low-fat wagon because it leaves them too hungry, too often. Hunger is a powerful, primal urge that is difficult to deny voluntarily for long. It’s not a character flaw, it’s just biology. Low-fat diets are generally carbohydrate-rich, and carbohydrates do a poor job keeping us full. Protein, on the other hand, is the most satiating of the three macronutrients—protein, fat, and carbs. Protein is the nutrient that will make us feel full, make us stop eating, and keep us feeling satisfied for hours. Fat is second, and the combination of protein and fat is extremely effective. Low-fat diets, low on protein and generous with carbs, are destined to keep us ravenously hungry, irritable, distracted, and generally no fun to be around.

When people fall off the low-carb wagon, my opinion again, it’s because we have been conditioned to view eating carbs as a natural and undeniable right. I’m not talking about spinach and broccoli, but simple, refined carbs like flour, white rice, sugar, and high-fructose corn syrup. A large body of evidence has shown that low-carb diets are effective and free of the disastrous cholesterol effects that many predicted. There is also extensive evidence that eating large amounts of simple carbs can lead to metabolic syndrome and obesity, but we are still immersed in a carb-loving culture. Behold the cookies in the break room, the cake at the birthday party, the popcorn at the movies, and the pizza while watching the game. Refined carbs of every size, shape, color, consistency, and temperature are ever-present and way too tasty to ignore. Avoiding simple carbs feels like punishment and we know we don’t deserve that. However, just like video games are a blast but don’t build much character, simple carbohydrates are tantalizingly delicious but non-nourishing, .

Low-carb versus low-fat redux

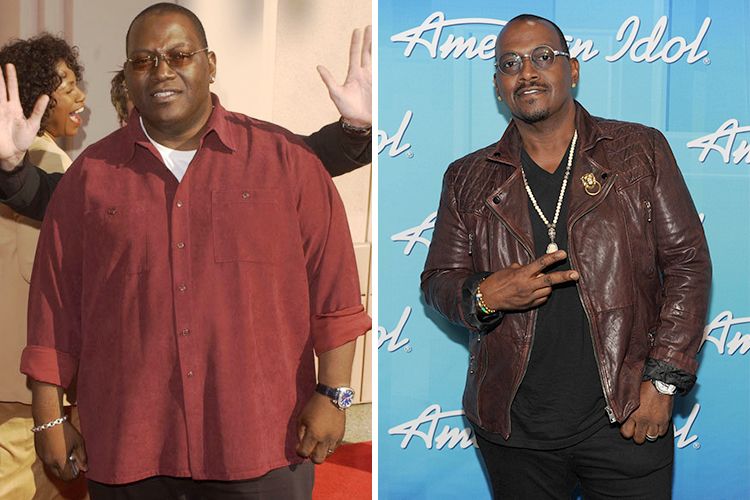

So despite the challenges, if we commit to adhering to a diet plan no matter what, which should we choose? Are they both destined to fail? Of course not. Just look at the before and after pictures all over the web. We can lose weight and improve our heath as assuredly as we can gain it and become unhealthy through diet and activity choices. It’s just that it is tremendously hard. Especially because it requires a permanent sea change from the typical American diet. Adopting either strategy requires consistent planning, steely determination, and heroic self-restraint. If we are going to invest this kind of energy in either strategy, it would sure be nice to know which is most effective for long-term weight reduction/maintenance and protection from disease. Is Pagoto right in concluding that low-carb and low-fat diets are both valid choices?

The Evidence

Several recent meta-analyses have reported that both low-carb and low-fat plans can indeed produce similar short-term results. While major media outlets often hype isolated scientific findings only to report contradicting studies a week later, meta-analysis allows more comprehensive conclusions by combining multiple studies. With adequate numbers of well-designed trials to draw from, meta-analysis can provide evidence of the highest quality. If the source studies are flawed, meta-analysis conclusions are dubious. “Garbage in, garbage out” is too harsh a phrase for the analyses in question, but the reliability of meta-analysis conclusions depends on the quality of the studies included.

Let’s take a brief look at the 4 meta-analyses Pagoto cites as evidence that diet debates should end. They were all published within the last year.

A report from the British Journal of Nutrition looked at 14 trials comparing very-low-carbohydrate diets to low-fat diets. Results showed that very-low-carb diets produced greater weight loss, greater reduction of triglycerides, greater elevation of HDL or “good cholesterol,” and decreased diastolic blood pressure. Very-low-carb diets also elevated LDL, or “bad cholesterol.” This latter effect was postulated to result from increased saturated fat consumption, which in a carbohydrate-restricted diet has been shown to increase large-particle LDL not associated with the same cardiovascular risk as small LDL particles.

A second report from the American Journal of Epidemiology looked at 23 trials comparing low-carb to low-fat diets. Results showed that both diets were effective for reducing weight and waist circumference. Both reduced cholesterol, triglycerides, blood pressure, insulin, and blood glucose. Low-carb diets produced superior elevation of HDL and better reduction of triglycerides, but less reduction of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol.

The third report from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition looked at 24 trials of calorie-restricted low-fat diets with high or standard amounts of protein. Results showed that the higher protein version produced more fat loss, better preservation of muscle mass, and better triglyceride reduction.

Lastly, another report from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition looked at 20 trials comparing different diets in people with type 2 diabetics. Results showed that low-carb diets provided better weight loss, blood sugar control, and HDL elevations compared to low-fat diets or even the American Diabetes Association’s own recommended diet.

Taken as a whole, these meta-analyses show that low-carb diets are more effective for losing weight than low-fat diets. The advantage is significant but not huge. According to these findings, we could expect to lose a few more pounds on a low-carb plans versus low-fat. Importantly though, dropping even a few additional pounds is known to reduce the risk of serious health problems like diabetes.

Both diets appear to have a generally beneficial effect on cholesterol, but the results with regard to raising or lowering LDL with low-carb diets are inconsistent. An adequate discussion on LDL subtypes and their implications for heart disease are beyond the scope of this article, but this topic remains an important area for further research. Cholesterol science as it relates to cardiovascular risk is a much murkier and controversial topic than popular discussion would lead us to believe. It remains an open question as to whether all LDL is “bad,” but there is evidence that small-particle LDL is and large-partcile LDL is not.

It’s important to note that these studies shed no light on potential differences between specific variants of low-carb diets, which can differ tremendously in the quality of food included. Paleo and “primal” diets espoused by people like Robb Wold and Mark Sisson are quite different from diets that simply reduce carbohydrates but allow protein and fat from any source. It may be that low-carb diets consisting of whole, organic, free-range, wild, and grass-fed sources have entirely different effects than factory farm and processed food versions. There is limited data suggesting superior effects with these variants, but we don’t have adequate research to know for sure.

The Verdict

It seems that important debates should end only if satisfactory conclusions can be made. Win, lose, or draw. While I agree with Pagoto that we need to figure out how to help people adhere to diets, there are too many problems with the existing studies to conclusively prove which diet we should be adhering to. The available studies have not provided the information needed to draw definitive determinations. They are simply not good enough, therefore the meta-anlyses are not conclusive enough. The authors of these papers, despite valiant attempts to answer the ideal diet question, catalog many of the problems and confounding elements in these studies in their own reports. Small sample sizes, short duration, selection bias, lack of blinding, and inadequate control measures—the list goes on and on. Put simply, the ideal diet debate is far from over.

Conducting airtight nutritional research is extremely challenging. It is especially difficult to implement high-quality diet trials in humans. We are not very good at tracking and reporting what we eat. People struggle to estimate portion sizes accurately, and the portion sizes may bear no relationship to how much people actually eat. Even if we measure everything to the last ounce, the calories and macronutrient amounts listed on the labels of commercially-prepared food are notoriously unreliable. If we are eating whole, fresh foods there may be no labels at all. We also fib and conveniently forget to record things (what Halloween candy?). So even our best attempts at this are suspect. Data on food intake, however, is most often collected by this flawed method. This is the bane of most nutritional studies conducted outside the confines of a lab, and it’s the method employed by many of the studies included in the meta-analyses.

To get around this problem, we can confine people in tightly controlled environments and feed them precisely measured diets. I don’t know anyone, however, who would volunteer for this long enough to acquire true long-term data, say 5-10 years. We don’t even like jury duty for a single day. And if we did find willing subjects there could be no blinding. Subjects would know what kind of food they were eating, thus removing one of the elements of highest-quality research.

More importantly perhaps, the dropout rates were huge in the studies included in the meta-analysis. Within 6 months some of the studies had lost 40% of their participants. Given that there are already important differences in people who agree to participate in studies versus those who decline, a built-in selection bias that can skew results, it’s hard to judge long-term results with ever dwindling numbers of participants. These studies were not designed to last long enough to begin with. Accurate assessment of long-term diet success and protection from disease likely takes decades, not a few months or even years.

The high dropout rate in the studies takes us back to the issue of adherence. Why is the dropout rate so high? Probably for the same reasons people quit diets in the real world. Obesity is a highly complex problem with contributing factors well beyond food choices. These include economic factors, genetics, learned behaviors, environmental conditions, hormonal function, and psychological influences. We cannot expect a prescribed way of eating to solve all these issues. However, this does not mean that there is no ideal way to eat. It does not mean that low-carb and low-fat diets are equivalent even if low-quality studies suggest they are. Maybe they are, and maybe the best strategy varies from one person to the next, but we haven’t proven this yet. Much more research will be needed to answer both questions —is there an ideal diet and how do we adhere to it? The two go hand in hand and both are both critical to solving obesity.

Any call for further dietary research that achieves a quantum leap in quality is a tall, perhaps unachievable, order. It would require astronomical investments of time and money. It would challenge powerful commercial, industrial, and political interests. However, for a generation of people who may not live as long as their parents, we cannot afford not to stop trying.